Sustainable Urbanism: Green alone does not define sustainability. True resilience emerges when water, heat, soil, and built form operate as coordinated systems over time.

Green, on its own, is not a system. And systems, unlike symbols, reveal themselves only after use.

Green has become the most reassuring colour in contemporary development. A row of trees, a planted terrace, a vertical garden climbing a facade, all signal care, responsibility, progress. Yet many of the places that look the greenest remain deeply uncomfortable to live in.

This is not a failure of intention, but of definition. Sustainability, when reduced to what can be seen, often ignores what must quietly endure – water movement, heat, soil, maintenance, and time. What looks ecological in the first year can become extractive by the fifth.

Green, on its own, is not a system.

And systems, unlike symbols, reveal themselves only after use.

Sustainability is often described through outcomes rather than processes. Green cover, shaded walkways, landscaped roofs, and tree counts are presented as evidence of ecological intent. While these elements matter, they are only fragments of a much larger system. On their own, they say little about how a place performs over time.

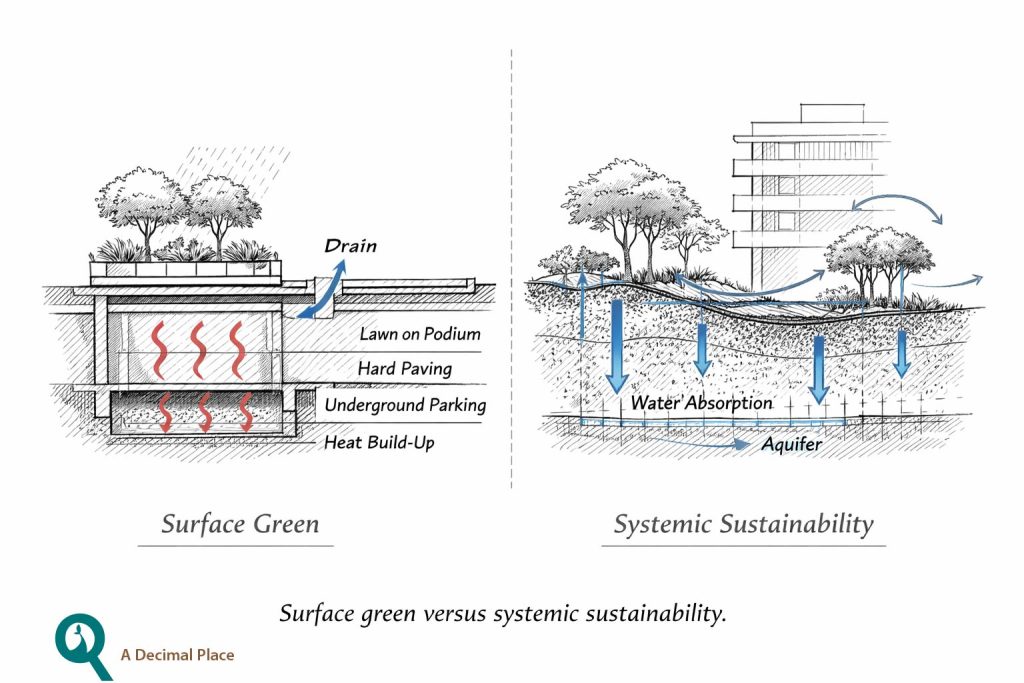

True sustainability is not visual. It is operational. It concerns how water moves through land, how heat is absorbed or released, how materials age, and how human behaviour adapts within a space. These forces are largely invisible, which makes them harder to market and easier to ignore. Yet they determine whether a project remains resilient or slowly deteriorates beneath its green surface.

The challenge is not to add more green, but to ask better questions.

Many developments fail not because they lack greenery, but because greenery is asked to compensate for deeper inefficiencies. Trees are planted where the soil cannot support them. Lawns replace permeable ground. Irrigation systems work overtime to sustain vegetation that does not belong to the local climate. The result is an environment that looks sustainable while consuming more resources than it saves.

Sustainability, in its most meaningful sense, is about alignment. Climate, soil, water, materials, and daily use must work together rather than in isolation. When these systems are coordinated, green elements enhance performance naturally. When they are not, green becomes decoration.

The challenge, then, is not to add more green, but to ask better questions. How does the site drain during heavy rain. Where does heat accumulate during peak summer. What maintenance will the landscape demand five years from now. Sustainability begins when design responds to these realities instead of concealing them.

Green elements often enter a project later in the design process. Once building footprints are fixed and infrastructure is locked, the landscape is asked to soften the result. Trees are added to offset heat. Lawns are introduced to suggest openness. Vertical gardens are applied to façades to signal environmental intent. At this stage, greenery becomes corrective rather than structural.

This inversion creates predictable failures. When soil depth is insufficient, roots struggle and maintenance increases. When surface drainage is not planned, landscaped areas become waterlogged during monsoons and dry out during summer. When native conditions are ignored, irrigation and chemical inputs rise steadily. What begins as a visual promise turns into an operational burden.

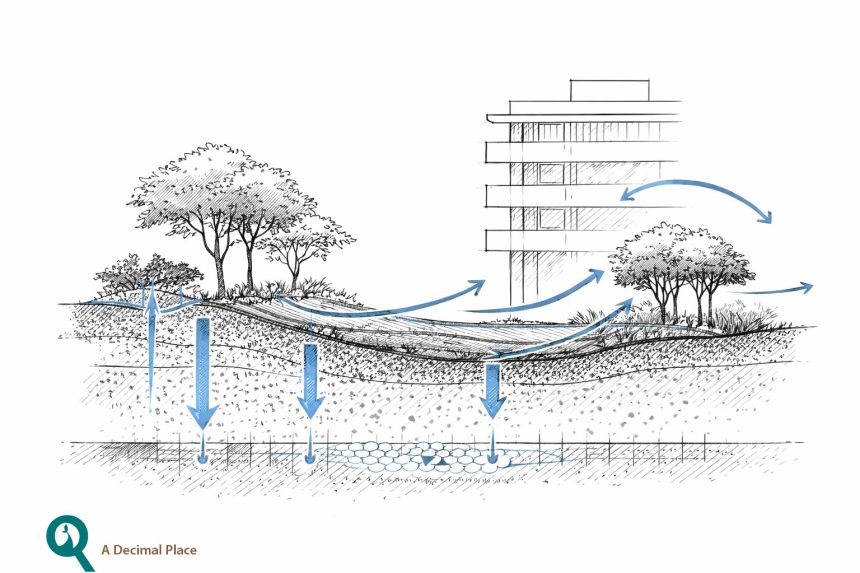

Water offers the clearest example. Many projects celebrate green cover while treating rain as a nuisance to be removed quickly. Hard paving dominates ground planes, forcing water into drains rather than soil. Landscaped pockets remain disconnected from natural percolation paths. In such environments, flooding and water scarcity coexist. The presence of green does not prevent either.

Heat behaves in a similar way. Shaded courtyards and planted edges can reduce ambient temperature, but only when supported by orientation, massing, and airflow. Without these, greenery becomes cosmetic. Heat accumulates in sealed podiums and enclosed basements, radiating upward despite planted terraces above. The landscape is visible, but the thermal logic is broken.

Long-term maintenance exposes these contradictions. Landscapes that depend on constant watering, trimming, and replacement are not sustainable systems. They are ongoing resource commitments. Over time, budget pressures lead to neglect. Lawns thin out. Trees decline. Green fades, leaving behind infrastructure that was never designed to perform on its own.

Effective sustainability works in reverse. Systems are established first. Drainage paths are mapped before paving. Soil depth is protected before planting is specified. Building orientation reduces heat gain before shade is added. In such contexts, green elements reinforce performance instead of compensating for its absence.

The difference is subtle but decisive. One approach treats nature as an overlay. The other treats it as a framework. Only the latter endures.

When landscape, water, and built form respond to one another, sustainability stops being claimed and starts being experienced.

Across cities and climates, the most resilient environments share a common trait. They rely less on visible markers of sustainability and more on systems that quietly regulate themselves. Long before sustainability entered the professional vocabulary, settlements evolved by observing how water flowed, where heat gathered, and how the ground absorbed or rejected rain.

In many older urban fabrics, green was never isolated as an object. It was inseparable from land and structure. Courtyards absorbed rain before it reached drains. Trees were placed where soil depth was naturally available. Open ground was continuous rather than decorative. These spaces endured not because they looked ecological, but because they worked with the limits of climate and terrain.

Contemporary urban development often operates at a different scale, with different constraints. Density, infrastructure demands, and regulatory pressures leave little room for such continuity. Yet some cities and projects have begun to reintroduce systems thinking, not by replicating traditional forms, but by restoring underlying logic. Permeable surfaces replace sealed ground. Landscapes reconnect to drainage networks. Built mass is arranged to reduce heat before shade is added.

These approaches rarely announce themselves. They do not rely on visual abundance. Their success becomes evident over time, through reduced flooding, lower heat stress, and landscapes that mature instead of constantly being replaced. Sustainability, in these contexts, becomes less about appearance and more about performance.

What this reveals is a shift in emphasis. Green is most effective when it is not treated as an addition, but as part of a larger environmental conversation. When landscape, water, and built form respond to one another, sustainability stops being something that is claimed and starts becoming something that is experienced. A resident notices it not through signage or statistics, but through small absences. Water that does not pool after heavy rain. Courtyards that remain usable in peak summer. Trees that deepen in shade rather than struggle to survive. The system works quietly, and in doing so, recedes.

Green earns its meaning only when it is supported by systems that last.

Without that logic beneath it, sustainability becomes a surface condition, convincing at first glance and fragile over time.