Light, Air, and the Architecture of Ease

A comfortable room rarely announces itself.

It reveals itself slowly – in the way daylight drifts across a wall, in how air moves without asking permission, in the absence of effort it asks of the body.

We tend to credit comfort to finishes, furnishings, or climate control. But long before materials register, the senses respond to something more elemental. Light that arrives at the right angle. Air that circulates without noise. A space that neither presses in nor leaks away.

This is the architecture of ease.

Not a style, not a feature – but a condition created when light and air are allowed to follow their natural rhythms, guided gently rather than constrained.

This is the architecture of ease – not a style or a feature, but a condition shaped by how light and air are allowed to move.

The Idea

Ease in architecture is often misunderstood as generosity. Larger rooms, taller ceilings, and wider openings are assumed to translate into comfort. Yet many expansive spaces feel strangely demanding, while smaller ones feel calm. The difference lies not in size, but in how light and air are choreographed.

Human comfort is deeply sensory, and much of it operates below conscious thought. The body responds to contrast, movement, and rhythm before it processes form or function. Light that changes through the day helps us orient time. Air that moves gently across a space signals freshness and safety. When these elements behave naturally, the mind relaxes. When they are over-controlled or absent, unease sets in, even if the room appears visually perfect.

The architecture of ease does not attempt to dominate these forces. It works by anticipation. Where will the morning light fall? How will heat escape in the afternoon? Which path will Air choose if it is given more than one option? These questions shape comfort far more reliably than finishes or mechanical systems.

In livable spaces, light and air are not utilities added after planning. They are primary design inputs. Walls, openings, and volumes are arranged to guide them gently, allowing variability rather than uniformity. Ease emerges not from precision alone, but from accommodation – a willingness to let spaces breathe, shift, and respond.

This is why ease feels intuitive when it is present and exhausting when it is not. The body is remarkably sensitive to environments that cooperate with its needs. When architecture aligns with these quiet expectations, comfort stops feeling engineered and begins to feel inevitable.

The Decode

Light and air are rarely experienced as absolutes. They are felt in gradients – in the way brightness softens toward the edges of a room, in how air cools one corner while leaving another still. Comfort lives in these variations. Uniformity, despite its visual appeal, often flattens experience.

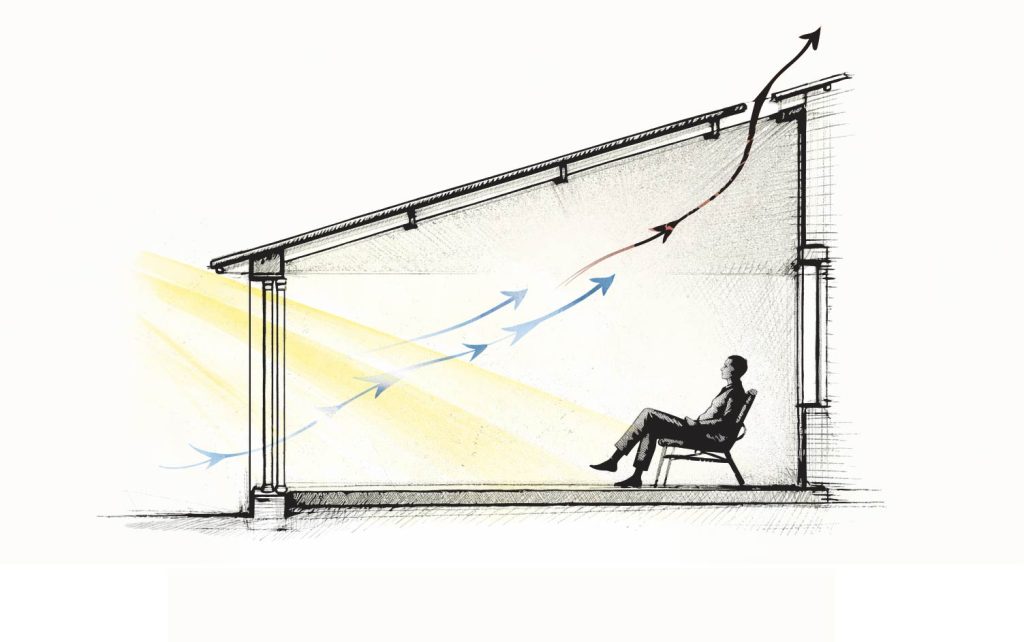

Consider light first. Spaces that feel calm rarely rely on brightness alone. They depend on direction. Light that enters from one side gives the eye something to rest against. It creates depth, shadow, and orientation. When light arrives evenly from all directions – through excessive glazing or overhead sources – the room may appear luminous, but the body struggles to settle. The absence of shadow removes cues of scale and distance. The eye works harder, even when the room looks pristine.

Daylight does more than illuminate space. It anchors time.

Daylight that changes through the day performs another quiet function. It anchors time. Morning light stretches horizontally, inviting movement. Afternoon light descends more steeply, slowing activity. When architecture allows these shifts to register – through window placement, depth of opening, or layered thresholds – occupants remain subconsciously aligned with the day’s rhythm. Artificial lighting can replicate brightness, but it rarely restores this temporal awareness.

Air behaves with similar subtlety. Comfort does not require constant movement; it requires the possibility of movement. A room with no air exchange feels stagnant even before temperature rises. Conversely, a space where air can enter, rise, and escape creates a sense of relief – regardless of size. Cross-ventilation, stack effect, shaded inlets, and pressure differences are not technical embellishments. They are spatial decisions that determine whether a room feels alive or sealed.

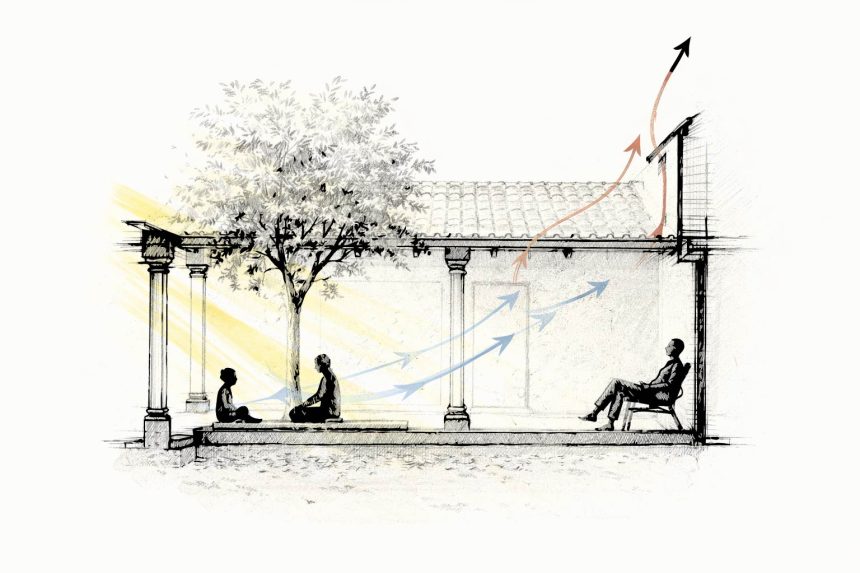

Traditional architecture understood this instinctively. Openings were placed not to frame views alone, but to create paths. Courtyards acted as lungs, drawing warm air upward. Verandahs filtered wind, slowing it before it entered living spaces. Ceilings varied in height to guide heat away from where people gathered. None of this was visible as design intent, yet its absence is immediately felt in modern interiors that rely entirely on mechanical correction.

Ease emerges when light and air are treated as moving elements rather than quantities to be maximised. Windows become instruments of moderation. Depth replaces exposure. Transition spaces such as verandahs, buffers, and shaded edges absorb excess before it reaches the interior. What results is not stillness, but balance.

The most comfortable spaces do not demand attention. They allow the body to relax into them because light falls where it should, and air moves where it must. Architecture, in these moments, does not assert itself. It recedes – and in doing so, it works.

The Context

Across climates and cultures, the most enduring forms of housing share a quiet commonality. They treat light and air as collaborators, not problems to be solved. Long before environmental simulations and performance metrics, buildings were shaped by watching how sun and wind behaved across seasons.

In warm regions, homes opened inward. Courtyards moderated extremes, allowing light to enter without glare and air to circulate without force. Walls were thick not for monumentality, but for thermal patience. Verandahs and shaded thresholds slowed the transition between outside and inside, giving the body time to adjust. These were not stylistic gestures. They were environmental negotiations refined through use.

Modern housing, particularly in dense urban contexts, often reverses this logic. Light is invited in abundance, air is sealed and replaced mechanically, and comfort is expected to remain constant regardless of time or weather. The result is efficiency without ease. Spaces perform well on paper but feel disconnected from the day unfolding beyond their walls.

Some contemporary architects are beginning to re-learn these older lessons, not by copying forms but by restoring intent. Openings are sized for control rather than spectacle. Buildings are oriented to receive morning light while deflecting afternoon heat. Transitional spaces return, quietly, as buffers that protect interior calm. These projects succeed not because they look traditional or modern, but because they acknowledge that comfort is situational.

What emerges from this comparison is not a preference for past over present, but a reminder. Architecture that supports ease does not fight climate, time, or human behaviour. It listens first. When design begins from observation rather than assumption, light and air stop being managed and start being understood.

Ease is not designed into walls or systems.

It appears when architecture allows light and air to behave as they always have — moving freely, changing gently, and reminding us that comfort begins with cooperation, not control.