Comfort begins long before we notice softness or style.

It lives in distance, rhythm, and the unseen mathematics that make a space feel right.

The Hidden Geometry of Comfort explores how proportion, perception, and culture quietly shape the places we call home – from the golden ratio to the humble verandah.

The Hidden Geometry of Comfort

By AIQYA Research

Field Notes – Essays on livability, design, and the evolving language of human habitats.

We often mistake comfort for softness. Cushions, lighting, and colour palettes create a sense of welcome, but they only skim the surface. Beneath what we call comfort lies something far more deliberate: geometry. The most livable spaces are not those filled with objects but those shaped by a kind of quiet precision, where distances, proportions, and alignments fall naturally into place.

Comfort is not decoration; it is spatial empathy measured in metres and light.

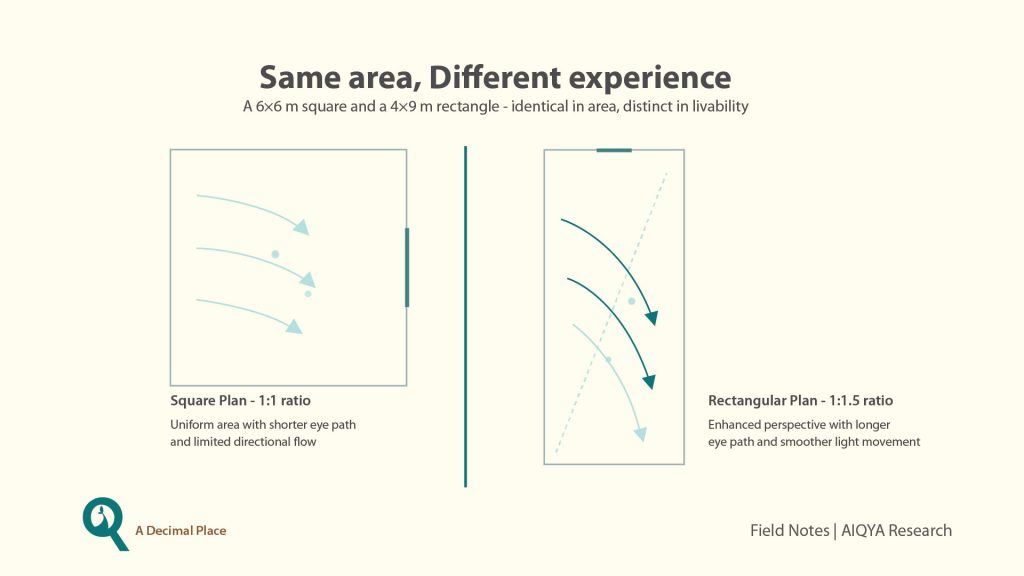

Same Area, Different Geometry

A 6×6 m square and a 4×9 m rectangle – identical in area, distinct in livability.

(Uniformity may feel contained, while direction creates rhythm.)

Walk into a room that feels comfortable, and your body relaxes before your mind understands why. The geometry is invisible, yet it works on you instantly. A hallway that is too narrow quickens your stride. A living room that is too square makes conversation sound flat. A space that is just slightly longer than it is wide slows the rhythm of movement and softens speech. This is the choreography of design that we seldom notice but always respond to. Comfort is not decoration; it is spatial empathy measured in metres and light.

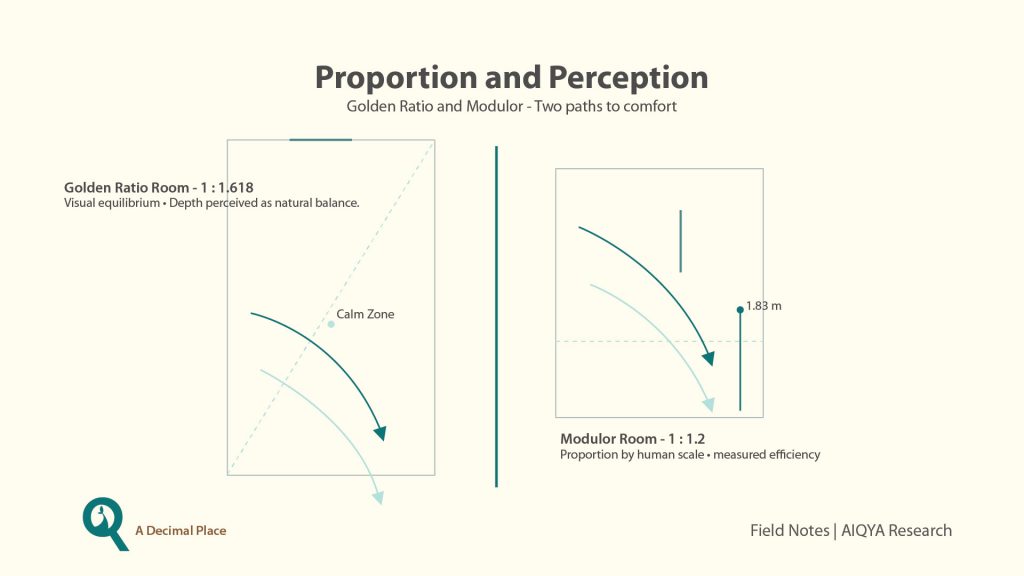

Across time, architecture has chased this idea that beauty and balance come from proportion. The Greeks and Romans codified it through symmetry and the golden ratio, an elegant constant of roughly 1:1.618 that recurs in temples, paintings, and even seashells. Vitruvius wrote that buildings should mirror the proportions of the human body. Centuries later, Le Corbusier reinterpreted that idea in his Modulor system, an attempt to align the scale of architecture with human height and movement.

Yet while mathematics endured, real comfort often strayed. The golden ratio was never a fixed formula for ease; it was an aspiration for harmony. Human comfort, unlike geometry, resists perfection. It shifts with climate, culture, and habit. The dimensions that feel natural in Athens differ from those that feel right in Ahmedabad. Our sense of proportion is learned through living, not drawn from blueprints.

Proportion and Perception

The Golden Ratio and Le Corbusier’s Modulor both sought harmony – one through nature, the other through human measure.

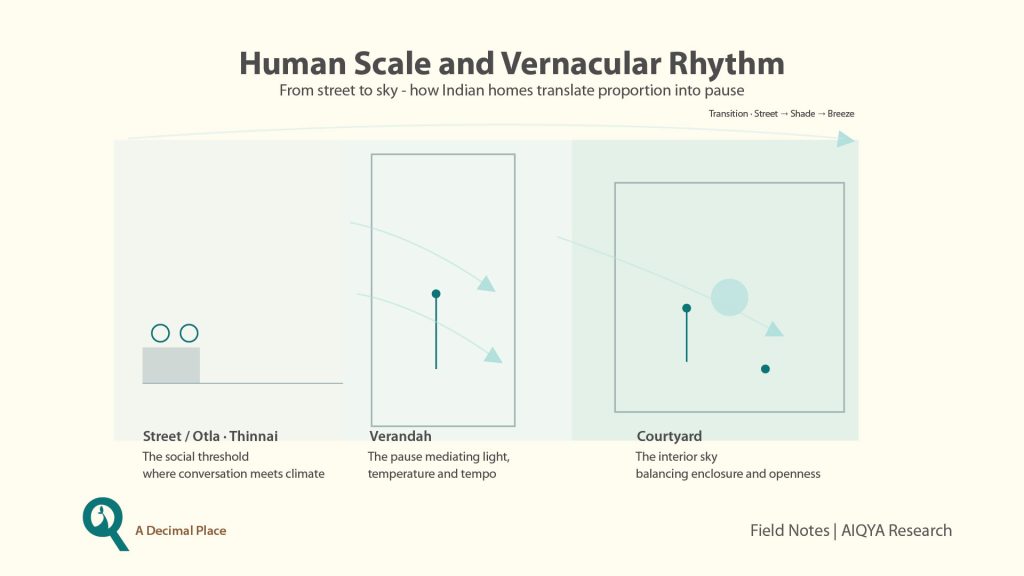

Traditional Indian homes understood this instinctively. Courtyards, verandahs, and passages followed the logic of climate before that of geometry. Courtyards were narrow enough to let morning light reach the floor but deep enough to hold cool air through the afternoon. The verandah measured not grandeur but use, wide enough for two charpoys, shaded enough to host conversation without glare. The angans and otlas (or thinnais in the south) of old homes were not designed for symmetry; they were designed for rhythm.

That rhythm extended to the invisible. Ceiling heights lowered gradually toward the kitchen to trap warmth. Inner rooms aligned diagonally with windows for ventilation and privacy. Spaces grew or shrank according to how people gathered, prayed, or rested. What guided design was not ratio but routine, the cadence of daily life turned into form.

The mind relaxes when geometry supports behaviour.

Modern housing often inverts this relationship. The logic of saleable area replaces that of lived proportion. Walls shift to satisfy spreadsheets rather than sightlines. Corridors narrow to meet efficiency metrics, and rooms widen without purpose. On paper, these spaces look rational, but in life, they rarely feel generous. Movement becomes mechanical, and light feels misdirected. The invisible geometry breaks down.

Studies in environmental psychology explain why. Humans subconsciously prefer spaces where width and depth fall within certain ranges, typically between one to 1.3 and one to 1.6. These ratios allow both orientation and openness; they let the eye travel without losing focus. When the balance is lost, when rooms become too long or ceilings too low, our bodies register unease. We call it “vibe”, but it is really a neurological response to proportion. The mind relaxes when geometry supports behaviour.

Proportion, flow, and alignment; these three quiet elements determine how space feels. Proportion defines relationship, flow allows movement, alignment ensures light and air follow the same logic as people. Together they form what could be called the anatomy of comfort. A home may have perfect finishes and expensive materials, but if its geometry is careless, the experience remains incomplete. The finest marble cannot correct a misplaced window.

Some architects are returning to this order, starting with human motion instead of wall placement. They map how light shifts during the day, how people move from cooking to conversation, how furniture shapes pause and interaction. Only then do they draw boundaries. In these homes walls fall away from habit rather than dictate it. You can sense it immediately: a subtle naturalness, a spatial tempo that feels intuitive.

Human Scale and Vernacular Rhythm

From street to sky -how Indian homes translate proportion into pause.

(Otla · Verandah · Courtyard)

This approach echoes an older philosophy that modern design often forgets – measure by experience, not by metric. The act of design, when stripped of marketing jargon, is the act of listening to climate, to body, to time. Vernacular builders did it without instruments. They watched shadows, measured footsteps, and built from observation. Their geometry was not golden, but humane.

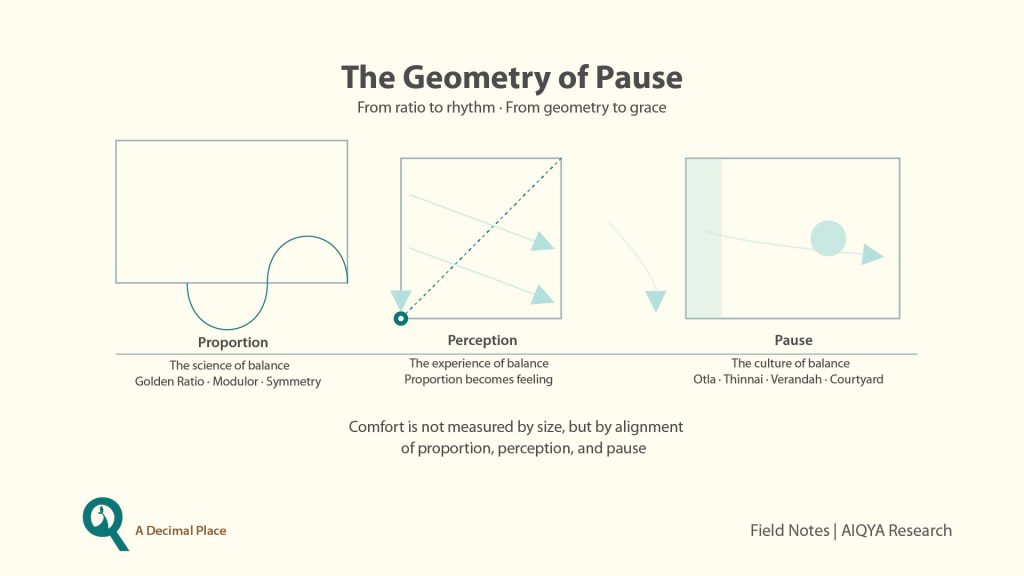

The Geometry of Pause

From ratio to rhythm. From geometry to grace.

What the ancients achieved by instinct, today’s designers can measure and refine with data. Digital simulation can model daylight penetration, airflow, and acoustic diffusion. Yet the challenge remains the same: how to translate precision into peace. Numbers can quantify performance; they cannot guarantee ease. The geometry of comfort lies somewhere between algorithm and empathy.

We do not inhabit walls or materials. We inhabit distances.

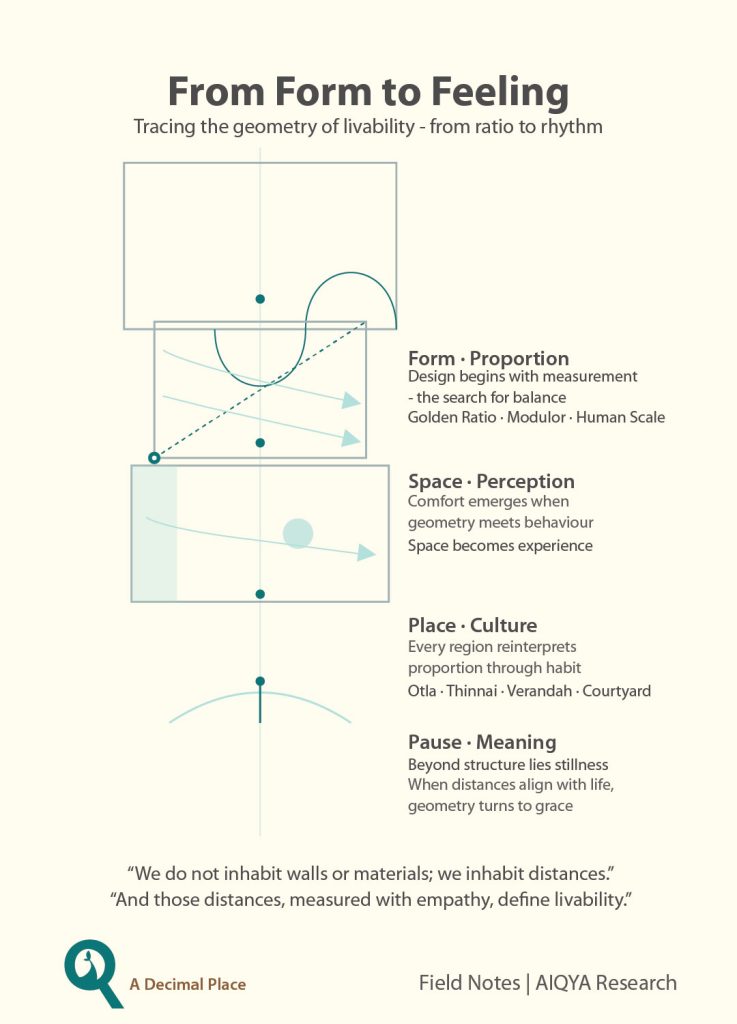

From Form to Feeling

Tracing the geometry of livability – from proportion to perception, from form to feeling.

We do not inhabit walls or materials. We inhabit distances.

And those distances, when measured with intelligence and feeling, turn geometry into comfort.

Field Notes is AIQYA’s ongoing journal on livability, design, and the evolving language of human habitats.

Subscribe to receive new essays every week at aiqya.com.